Things of Modernity

From agriculture to architecture, from household appliances to the metropolis, the beginnings of the broad reconfiguration of the built environment in Europe (and further afield) can be traced back to the various industrial developments and their outcomes in the nineteenth century. The factors that widely transformed society at this time were less a set of formal accomplishments in the form of auteur architecture, but rather a set of new fields of scientific expertise (e.g. hygiene), processes (e.g. electrification or access to water), and expert knowledge (e.g. the professionalisation of architects, engineers, and urban planners). These new fields allowed for the regulation of the environment through a series of systems, devices, and techniques. In turn these reconfigurations brought a comprehensive reorganisation of architecture and urban planning: how it was constructed, how it was controlled, and how it was understood amongst the various practitioners and the users of the built environment.

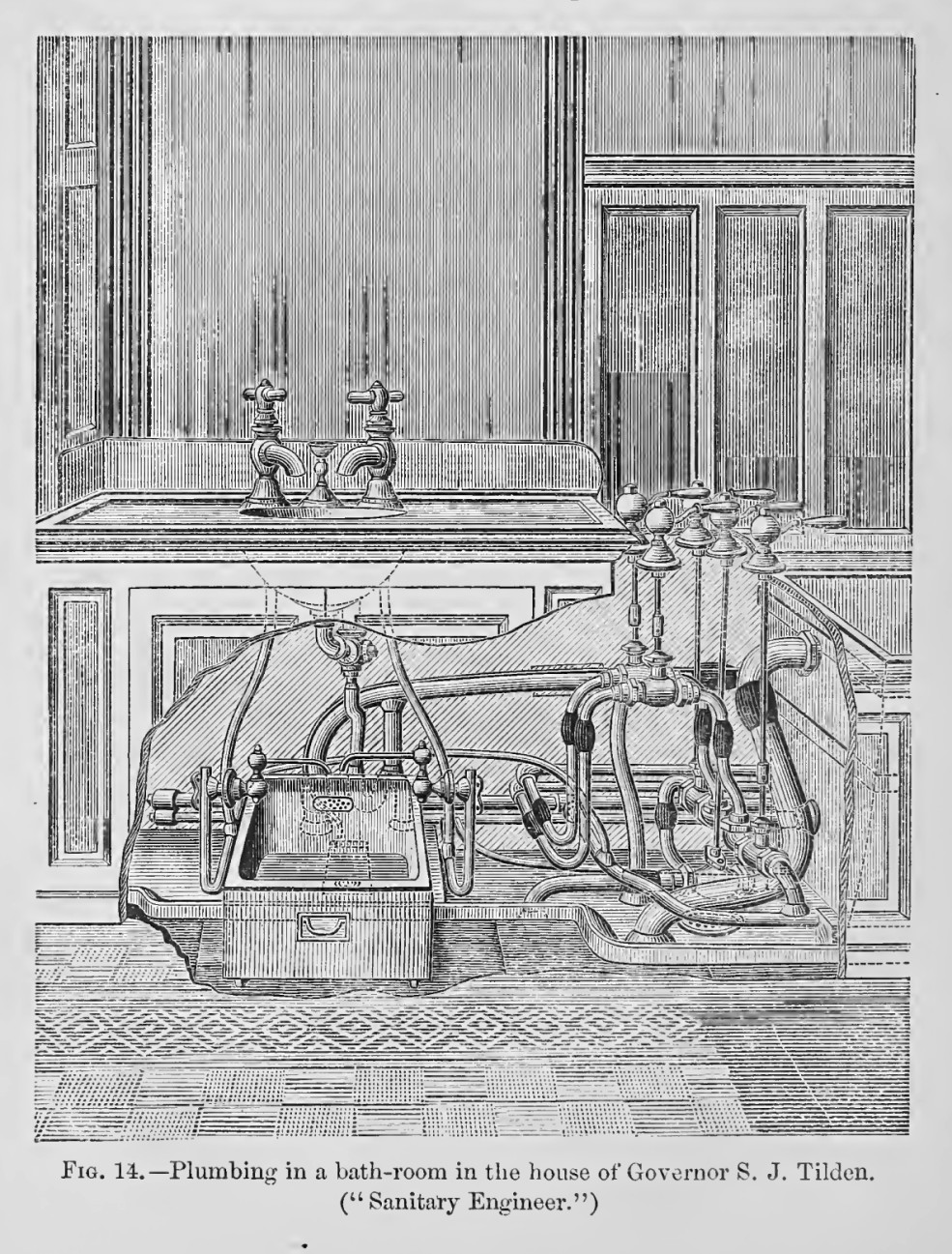

One central hypothesis is that these changes can be traced through the various scales at which architecture operates, ranging from the planning of infrastructure and urban development to the design of individual buildings formed from an assemblage of regulations, techniques, and technical devices, each with their own fields of discourse, systems of knowledge, and constellation of products. Across the period in question individual devices and networked systems, such as the dumbwaiter, the bell circuit, the water pipe (and its supply), the kitchen or the toilet, gradually incorporated themselves into the body of the building. In contemporary buildings these formerly independent technical objects become concrete as they form part of a whole technological ensemble, where the difference between apparatus and building, the users and the object used are interdependent. Not only have these transformations changed our understanding of architecture, they have also changed the way individuals and social groups experience the built environment. Therefore, these transformations are not only of a technical nature, they both reflect the rationale of increasingly refined technological systems and also span a discursive arc between contradictory notions of modernity: on the one hand the importance of comfort, security or hygiene, and on the other central role take by the disciplinary techniques and mechanisms of social control.

Such ideas, which serve to structure and organise space, are made manifest in the numerous apparatuses that complemented modern buildings, cities, and villages. In the revolving door the inclusionary and exclusionary mechanisms of the metropolis; with the elevator the negotiation of socially and/or functionally organised spaces within a multi-storey building; with the garbage chute the different means to treat waste within and outside a building; and in the letter box the medial networking of individuals, groups, and institutions. Therefore, to analyse these objects only from a technical perspective or see them simply as representations (of taste, desire, progress), does not allow for satisfactory analysis into the complex networks of actors involved in their development, design, or regulation. Instead, to do justice to the multifaceted dimension of these objects, which have shaped our environment in the last 200 years, the research project places these objects, the “things of modernity”, at the centre of its study.

The overall aim of the project is to propose a new reading of modern architecture (1850-20XX), starting not with the ever-changing “heroes” or canonical “pioneers”, nor the “key buildings”, but with a constellation of ‘things’ that shaped modern life: from the clock and the bed, to the toilet and the kitchen, to the radiator to the revolving door. The common tropes of modern architecture such as the piloti, the curtain wall, and the I-beam will not be separated from concrete examples, instead they will be studied in their historical contexts, considered alongside new examples from a wide range of sources, and problematized to help explain their role in the construction of the modern condition. In particular the project will examine the historical and theoretical instruments that shaped modern architecture. It will do this by analysing in an exemplary way the different machines, spaces, constructions, materials and elements that were developed, deployed, and conceived by the various stakeholders in the built environment. Through workshops and symposium held during the course of the project, it will engage with others scholars working in the fields of the environmental history, technology, and politics, as well as historians of material culture, design, and urbanism.